- Tue 17 December 2019

- Python

- #beginner, #education

Kids on Python is a kids oriented introduction to programming workshop I prepared after having that thought in my mind for quite some time. In early 2019, a close friend came to me looking for ways of initiating one of his kids to computer programming. After countless discussions, thinking things through down to the most tiny details, figuring out which skills we might be taking for granted and either avoiding their need or including them in the journey, at some point, I finally sat down and wrote the thing.

Materials

The workshop materials — teacher guide, kids’ cheat sheets and experiments guide, and more — are available under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license, in both Portuguese and English.

Materials

The workshop materials — teacher guide, kids’ cheat sheets and experiments guide, and more — are available under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license, in both Portuguese and English.

Assumptions

Assumptions can be somewhat dangerous traps in teaching processes, especially with kids. There’s no way you can go with a “let’s meet halfway” attitude: you’ll really want to grab their attention and understanding from whichever point they are at, at all times. Again, with kids, that becomes even more important.

How do you keep them engaged, giving them enough freedom to be creative, while ensuring they actually learn something in the process? I’m positive that educators around the world have been thinking about these challenges and, most probably, applying (and experimenting with?) all sorts of techniques, with varying degrees of success. There’s bound to be thousands of books on the subject and, while I wouldn’t call my self an authority on it, not by any stretch of the imagination, there is one thing that strikes me as very clear: learning is easier when unnecessary barriers are removed. That’s where assumptions come into play: what feels natural and obvious to you, might be completely alien to someone else. I’ve given this a lot of thought.

For this workshop,

kids are assumed to have very basic computer usage skills:

launching and terminating programs,

moving and sizing windows around the desktop,

basic typing,

and nothing else.

Additionally,

they are assumed to have some degree of maths skills,

being familiar with both integer and decimal numbers and arithmetic,

including negatives,

as well as being familiar with the < and > comparison operations.

Everything else is progressively laid down for them:

typing in “funny characters” like the much used #, :, or _ symbols,

saving and loading files,

learning that * and / stand for multiplication and division,

and even learning about cartesian coordinates.

Then there’s the aspect of language — not Python, but their native speaking and writing language, instead. While I wouldn’t say that knowing English is a strict requirement (or assumption!) for a kid to benefit from the workshop, I’m convinced that basic familiarity with the English language will significantly lower some barriers. Not only are Python keywords and library functions English-based, but so are many interesting valid argument values for things they will play with, like colour names.

Syllabus

In planning the syllabus, I started out with two things: the skills assumptions I just described, on one hand, and the key learning objective, on the other. The syllabus would then guide the journey from one to the other, progressively filling in the blanks, if I may use the analogy.

But what should the key learning objective be? Would there be any other, non-key objectives? If so, which? Again, I gave this some very serious thought and boiled it down to:

While this was my key objective, and a very powerful lesson you don’t easily forget, I figured that by itself it was both too abstract and too big. I thought, thus, that that would be my implicit key objective: nowhere throughout the workshop would I be claiming or exposing such idea, other than, maybe, in a friendly, welcoming chat on “how to you think computers work?”, or trying to answer a question like “are computers clever or dumb?”. With that in mind, wondering how to build something concrete that would guide us through the workshop, I established two additional, non-explicit, objectives:

-

Everyone should have fun.

Lots of it. Having fun removes fears and helps with engagement. Having fun is really important. -

Everyone should come out of it with a strong feeling of accomplishment.

Kids should want to go back to their families and friends saying “look what I did, isn’t it awesome?”.1

This was still a bit vague, but I felt I had framed it just right. From there, I progressively added objectives and constraints, while trying to come up with a concrete journey. The main things I thought about were:

-

We should create an interactive game.

Games can be engaging and fun, while stimulating creativity. High potential to contribute to a great sense of accomplishment. -

Avoid “terminal based” input and output.

While Python itself is a text based programming language, using “terminal based” input and output might not be the best way to introduce kids to programming. Terminals are alien to most beginners and, worse, can be felt as something very boring.2 -

Less is more.

How much Python do kids need to learn? Will we use modules in the Standard Library? What about third party ones? The smaller the set of ingredients is, the easier it will be to learn and experiment. Too small of a set, of course, can be unnecessarily limiting.

The turtle module

The motivation for using the turtle module was pretty high from the start.

First and foremost,

I figured that the value of having cross-platform,

interactive,

REPL-based (if wanted),

graphical output was paramount.

Not having to deal with installing third-party modules,

simplifying the workshop computer setup procedures,

was another important factor.

Once I discovered its widely unknown, multi-turtle, visual and input abilities, enough to create an interactive game, I was set.

With an eye on all of this,

I then delved into the Standard Library,

hoping that the included, cross-platform GUI

turtle

module could be used to create an interactive game.

I explored the documentation, played around with it for quite while, pushing it to its limits and, fortunately, figured out that indeed it could! Not only did it support the traditional, LOGO inspired, turtle-based graphics, but also — surprise! 😊 — it supported multiple turtle instances, including using GIF images for individual turtles (making them great candidates for game character sprites), and even keyboard and mouse-based input.

Supporting a “less is more” approach,

focusing on the turtle module would thus allow me to create a continuous journey,

from the very first steps,

typing a few turtle instructions at the REPL,

till the end,

creating a multi-character, fully interactive game.

The turtle module

The motivation for using the turtle module was pretty high from the start.

First and foremost,

I figured that the value of having cross-platform,

interactive,

REPL-based (if wanted),

graphical output was paramount.

Not having to deal with installing third-party modules,

simplifying the workshop computer setup procedures,

was another important factor.

Once I discovered its widely unknown, multi-turtle, visual and input abilities, enough to create an interactive game, I was set.

Here’s the outline of what I’ve come up with, including the programming concepts kids were to be introduced to:

-

Welcome.

Let’s talk about computers, are they clever or dumb? Let’s play a physical game, no computers needed: kids will give me simple “walk”, “turn left/right” instructions guiding me to a specific corner (or door, or window!) in the room. At some point I’ll explicitly ask them to give me invalid or unknown instructions to which I’ll react negatively and with no movement at all. -

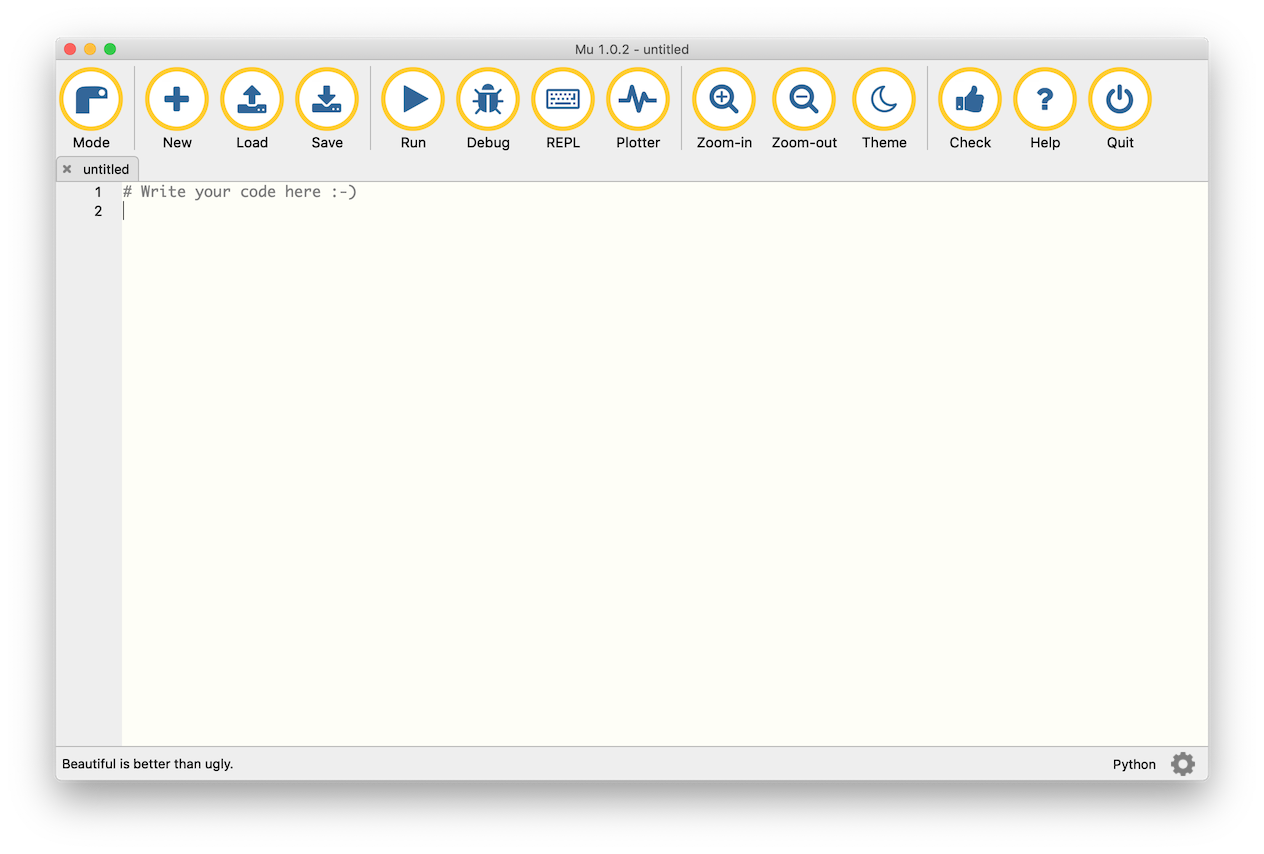

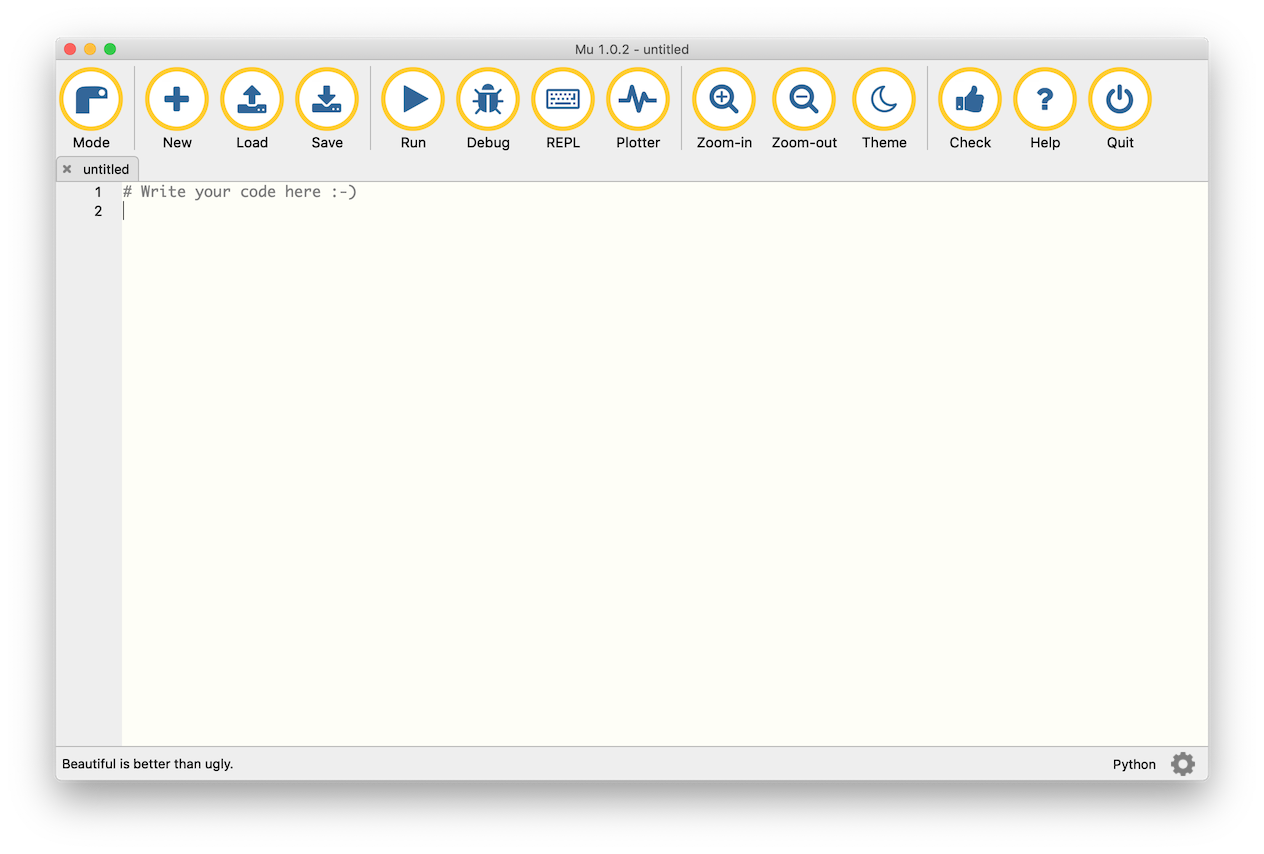

Our tools.

A careful walkthrough and exploration of the Mu Editor, the Python learning environment we would be using. Launching, closing, moving and sizing its window. Learning how to type commonly used Python characters, but probably unfamiliar to them. -

Numeric expressions.

Computers are very good at making calculations: try them out at the REPL and learn about the Python representations for the multiplication and division operators. Also, try out invalid input and become familiar with what Python does in such conditions. -

Interactive Graphics.

Explore the basics of turtle graphics at the REPL: drawing lines moving the turtle around, changing colours and line thickness. Understand the need for a program: saving, loading, and running it. The concept of sequential execution at play. -

First Programs.

Drawing a square. Drawing two squares, after copying and pasting code. Understanding variables as value placeholders: define once, use everywhere. Understanding the need for functions, to avoid repetition, and as a way to teach the computer about “new instructions”. Playing with random numbers and random choices. -

The Racing Game.

Learn how to respond to user input, making programs behave differently depending on it. Learn a fewturtlemodule “recipes” to do just that. Also learn how to make turtles look good, by using external GIF files. The racing game is a two-character game where the racers move from left to right, at random. The first to cross the finish line, wins. Introduction to the concept of conditional execution. -

The Player and the Beast Game.

The final, big project. Two characters, a player controlled one and a computer controlled beast move around in a grid. The player must capture the beast. Featured in my EuroPython 2019 “Don’t do this at work” talk (more on it below). -

Extension Activities.

Optional introduction to the concept of looping. Exploring the “Experiments Guide” with many different mini-projects, including several turtle based drawing ones, interactive mouse-based drawing, text based games, loops, and more.

Tools

One aspect I’m continuously faced with, in my professional activity on Python consulting and training, has to do with Python development and runtime environment setups, packaging and distribution. While I do agree that it’s a far from trivial topic, and that there are some serious underlying challenges, I believe that, in the majority of cases, the difficulties people face are due to their misunderstanding of “how things work”, at several different levels. A lot has been written on the subject and I myself sometimes feel compelled to writing more about it. I won’t do that now, as it would be completely out of context. I’ll instead link to an article I shared a while back on the fundamentals of Python Virtual Environments.

In this particular case, where kids would bring along the laptops they were to use, my main concern was in finding the simplest setup procedure possible, ideally, consuming no time at all of our workshop time together. Additionally, I had to come up with a solution to the intrinsic combination/separation of the Python runtime, on one hand, and a friendly text editor, on the other — something obvious to seasoned developers, but yet another learning barrier for beginners.

The amazing Mu Editor.

This is where the amazing Mu Editor really shines, having been created for this specific purpose and beginner audiences. A huge “thank you!” out to Nicholas Tollervey, the author, who has put countless hours of dedication it its creation, sharing it with the world, for free.

Whether on Windows or macOS3, a single file download, requiring no administrative privileges for installation, gets you a simple, no-frills, everything-in-your-face, minimalist Python development environment, including a text editor, a REPL interface, a visual debugger, and, importantly, the Python runtime itself. After installing Mu you are ready to go. No worries about installing Python (which version?) or choosing a beginner friendly text editor (which?) and installing that too, no worries about firing up a CLI shell to get to the REPL, yet another barrier in beginner learning processes.

The amazing Mu Editor.

With Mu you are set! And that’s precisely what we used. 😊

EuroPython 2019

An interesting by-product of this workshop is the Don’t do this at work talk I did at EuroPython 2019, in Basel.

After having ran the workshop with a group of four ~12 year-old kids across two days during a short Carnival school break back in March, as time passed, a few ideas started to settle down, becoming clearer and clearer in my mind — learning is important, having fun is important. Doing both is the best possible way of developing oneself, not only as a professional but, ultimately, as a human being.

In retrospect, maybe this is all pretty obvious, but I figured I had both an interesting story and a few provocative thoughts to share. More, I figured I had a message that bears repeating, in these rushed-up modern days, where it’s so easy to loose track of what’s really important. So, I reframed my workshop experience, went for a fun and hopefully instructive live coding session of a game we created, and wrapped it up with a few thoughts, including a serious “Should you do this at work?” question (spoiler: yes, you should!). Here’s its video recording:

Parting Thoughts

It has come to my attention that I could have done a better job at spreading the word on this workshop. After EuroPython, in Basel, several people reached out to me looking for the materials. I told them, back then, that I’d translate them to English, making them more world-wide accessible, and that once completed I’d publish them here. And that’s precisely what I did, during the summer. Since then, some people still got back in touch asking for the materials, while others were looking to review, discuss, understand some of the ideas I shared.

With all of that, I figured I’d write these words, describing some of my thought processes throughout the workshop preparation journey. Sharing knowledge is an incredible experience but it requires lots of thinking, lots of observation, lots of preparation. And repeating, repeating a lot. To observe more, to think and re-think more, to refine the learning journey.

When asked about the workshop in the abstract sense and its future, I rarely know how to answer. Will I run it again? I don’t know, maybe. I guess that’s something I’d like to do again, sometime. Could it be turned into a commercial venture? Again, I don’t know, but that’s not how I tend to see it — it’s more of a human nurturing thing for me, I guess. Maybe my only wish for its future is that someone, someday, may pick up on where I left and create something nice for a group of kids somewhere. And if they all have fun and learn one or two things along the way, then my mission is accomplished. I guess that’s it.

Thanks for reading these words.

Want to share your thoughts?

Get in touch and let’s talk.

-

In my observations, kids these days tend to use “awesome” a lot (or the equivalent “fantástico”, in Portuguese). I could go off on a rant on how such continued usage of hyperboles just wears off their own specific purpose — how would an effectively extraordinary thing, event, person, or idea be described then, when everything is claimed to be “awesome” or “fantástico”?!… But I won’t go there now. All in all, that is just kids being kids, and it’s perfectly fine. Maybe the issue lies with grownups like you and me. Think about it. 😉 ↩

-

Or very geeky, who knows? Maybe some kids will be excited to get a grasp on what a terminal is, like those “hacker things” they’ve seen in the movies! I decided to err on the side of caution, avoiding terminals and monochrome character based input and output. ↩

-

The Raspberry PI and other generic Linux distributions are supported too. In the former case, when running raspbian, the installation is a few clicks away, while in the latter, the installation process is not “beginner friendly” at all, so to speak. But it works! ↩